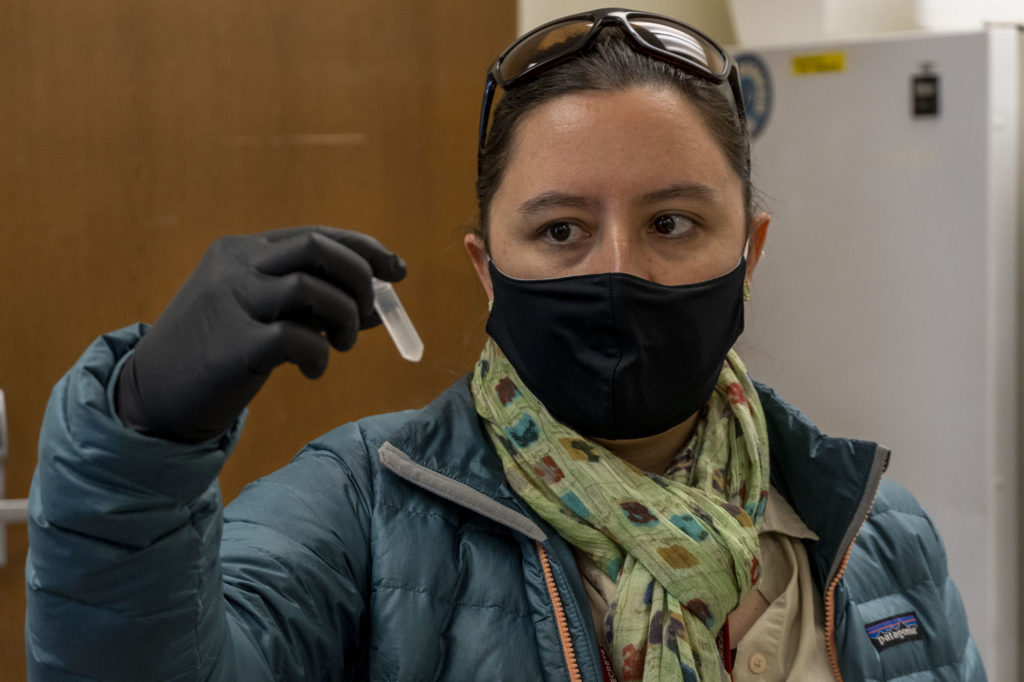

Profile: Catalina Cuéllar-Gempeler of HSU’s Biological Sciences Department receives prestigious National Science Foundation Award

Assistant Professor in the Biological Sciences Department at HSU, Catalina Cuéllar-Gempeler was recently awarded the prestigious Faculty Early Career Development Program Award from the National Science Foundation for nearly $1 million.

Specifically, she’s working with the carnivorous California pitcher plant and the Eastern pitcher plant which need to collect specific microbes to digest their food, like gut bacteria in humans, because these plants can’t make their own enzymes. She and her students will be looking into what these microbes are doing, how they live together and how they move.

Cuéllar-Gempeler first became interested in studying microbes after an experience that she had during an expedition in the Sierra Nevada of the Cocuy in Colombia. She and some classmates ended up getting separated from the main group and got lost in the mountains.

After running around trying to find the rest of their team, they stopped for a bit. Cuéllar-Gempeler realized that while she and her classmates were going through their own turmoil, the mountains, valleys and glaciers around them were all changing while her own life was changing.

“When we returned home, I couldn’t stop thinking about living creatures whose dramas unfold much more quickly than ours, and that is when I knew I wanted to know more about the microbes that share our world with us,” Cuéllar-Gempeler said in an email.

Colombia

Cuéllar-Gempeler is from Colombia, she spent half of her time in the city and the other half on her grandfather’s coffee and fruit farm. Being in the city allowed her to get an education and being on the farm helped her develop her love for nature and biology.

Some of her fondest memories from her childhood were eating fruit and riding horses on her grandfather’s farm and swimming and playing in rivers with her cousins.

Along with her family who she tries to see as regularly as possible, Cuéllar-Gempeler also misses the food from Colombia. She recalls being able to go to a street corner and buying arepas, corn and fruits. Recreating recipes or buying the same produce here just doesn’t taste the same.

“I feel like the sensory things, the sounds and the foods in your everyday life are hard to reproduce,” Cuéllar-Gempeler said.

Coming to the U.S.

In 2010, Cuéllar-Gempeler came to the U.S. to attend the University of Texas at Austin for graduate school. Initially, she thought that she would study here then go back to Colombia but the possibility of staying here was also in the back of her mind.

“It’s a process of acknowledging that you’re going to become an immigrant, and you’re going to be this mixture of identities,” Cuéllar-Gempeler said. “You go back and you’re not like everybody else, you don’t live there anymore. And you come here and you’re not like everybody else because you came from another place, so it’s interesting. It’s fun and weird at the same time.”

One of the things that helped her feel more comfortable in the U.S. was having a community of other Colombians and Latinos who she could relate and bond with and she also had friends outside of the Latinx community.

Education

Between 2002 to 2009, Cuéllar-Gempeler attended the Universidad de los Andes in Bogota where she earned a B.S. in biology and another B.S. in microbiology.

In 2010, Cuéllar-Gempeler attended UT Austin where she earned a PhD in integrative biology. Although she feels that her studies at the Universidad de los Andes prepared her well, grad school still came with its challenges.

“You’re joining a community of people that are super smart,” Cuéllar-Gempeler said. “Everybody’s an overachiever so you have to find your place in between a lot of smart people and figure out what makes us smart amongst them.”

Assistant Professor of botany at HSU, Oscar Vargas, met Cuéllar-Gempeler at the Universidad de los Andes in a class that he was the teacher’s assistant for and they also did their PhD at the same university.

“She was always excited to learn about plants and that always impressed me, that was really cool to have somebody that was more into microbes, but still really enjoy the botany class,” Vargas said.

After earning her PhD, she completed postdoctoral work at Florida State University.

HSU and Teaching Approach

Cuéllar-Gempeler came to HSU in 2018 after responding to a job advertisement for a microbial ecologist that nearly perfectly encapsulated everything that she was interested in. Out of the 501 faculty members at HSU in 2020, Cuéllar-Gempeler was one of 29 other Hispanic faculty members.

Cuéllar-Gempeler teaches general microbiology, microbial ecology and marine microbiology. Her specific area of research focuses on understanding how microbes associate with animals and plants.

Sandrine Thompson, a graduate student in Cuéllar-Gempeler’s lab studying microbial ecology, speaks highly of her advisor’s teaching.

“There’s two main things, one is a passion for teaching and really having students understand the material but also actually enjoy learning the material and going out of her way to make that happen,” Thompson said.

Parker Lund, another graduate student under Cuéllar-Gempeler, who is working on their masters of science in biology, appreciates the enthusiasm and energy that their advisor brings to class.

“The biggest reason I am at HSU is because of Dr. Cuéllar-Gempeler’s work,” Lund said. “Microbial ecology is a very new field and I think it’s exciting that her work tackles research questions from a very interdisciplinary perspective.”

Grant

The grant that Cuéllar-Gempeler received is awarded to academic role models who integrate both academic research and education into their work. Her research will focus on understanding how biodiversity and function are affected by the movement of organisms.

“I think the beauty of the grant is answering very relevant questions to how we think about microbes and diversity, but also bringing the students and the school into it. It’s not just me, it’s all of us,” Cuéllar-Gempeler said.

Cuéllar-Gempeler applied to a lot of grants before she got this one but she thinks we should normalize the idea of things not working out but it’s okay because you learn and improve.

“It’s not the end of the world, you don’t get accepted to places and you don’t get jobs and you don’t get grants, and that’s okay it’s part of the process,” Cuéllar-Gempeler said.

What’s next

According to Cuéllar-Gempeler, microbial ecology is a relatively new field of study and a lot of the understanding, observations and studies of the field have occurred just in the last five to 10 years.

Before then the technologies needed to study microbes, like genetic sequencing, weren’t very easily accessible.

Studying microbes is important to Cuéllar-Gempeler because they’ve been living on earth billions of years, they live inside us and play a clear role in our health and they’re responsible for transformation of nutrients, which no other organism can do.

In the summer, Cuéllar-Gempeler will begin running her research program most of the funding will go toward students, salaries and sequencing.

She is looking forward to seeing the results of the work and integrating the ideas of diversity and function and dispersal of organisms into broader scientific questions like animal behavior and even climate change.

“I’m really excited to get this grant going to get those answers and start really putting our feet into how can we use this information,” Cuéllar-Gempeler said.